The spiritual atmosphere of Ramadan has always been a source of inspiration for artists and literary figures. Take a look at how this special month has been reflected in various artworks and literary pieces from past to present.

Muslims across the world this year welcomed a markedly duller Ramadan than usual, owing to measures put in place against the coronavirus pandemic. In light of the measures, views of empty grand mosques, especially at the Kaaba, have replaced the colorful Ramadan images taken in previous years.

Throughout history, the month of Ramadan has held special significance in Islamic culture. It has also uniquely shaped art and literature as a result of the sudden shift it brings to social life.

In the past, the spiritual atmosphere of Ramadan would bring about a complete change in the public mood. This enthusiasm was to such a degree that during the Ottoman period, ambassadors and travelers from Europe could not help but write about the experience.

Ogler Ghislain De Busbecq, an ambassador from the period of Suleiman the Magnificent, told of how the month differed from any other, saying it was nothing like the festival atmosphere achieved in Europe, but that the Turks welcomed the month with a calm and dignity that he had not seen, with no extremities even after people broke their fasts. He underlined that Turks enjoyed a calm environment, while, in contrast, forms of entertainment were quite extreme at the end of similar fasting periods in Europe.

Every era has been marked by a unique atmosphere during Ramadan, with plenty of travelers having reported what they witnessed from their own perspective. In the 17th century, German theologian, minister and diplomat Salomon Schweigger also reported on the zeal of Ramadan in his memoirs. He especially pointed to what people did for street animals. “Street animals are given charity. Around 30-40 hungry and shabby cats gather in front of the mosque every day in the evening. The Turks come here to give meat and fried liver parts to cats. This counts as a very important charity. Dogs also get their share of charity. Some people buy a caged bird and release it, trying to do a good deed,” he said.

Later, French poet and literary critic Theophile Gautier, known as the founder of Parnasism, also comes to the fore as one of many Western artists quite bedazzled by the scenes on display in the imperial center over the course of Ramadan. While explaining what he experienced under the title of “A Night in Ramadan,” he describes the view he has seen from Passage Petit-Champs in Istanbul’s Beyoğlu district as follows:

“The view from this promenade was wonderful. On the other side of the Golden Horn, Istanbul gleamed like the crown of an Eastern emperor. The balconies of the minarets of the mosques were decorated with bracelets from oil lamps. Verses from the Quran, which appeared on the sky as if written on the pages of a holy book with letters of fire, from one minaret to another, were sparkling. Hagia Sophia, Sultanahmet, New Mosque, Süleymaniye … All the masjids of Allah, ranging from Sarayburnu to Eyüb’s ridges, were shining in brightness, declaring the formulas of Islam with fiery sentences. The crescent, with the star next to it, seemed to have embroidered the empire’s emblem on the sky. The waters of the bay further intensify these millions of luminous fluorescent sparkles by breaking them apart, cascading waterfalls made of precious stones melted in half. They say the truth always lies behind the dream, but here truth left the dream behind. In addition to this leap-long gigantic, blazing sheath, the 1001 Nights have lost their legendary charm, while the shimmering treasure of Harun Al-Rashid (the fifth Abbasid Caliph, who was also known as Aaron the Orthodox) blazes. Freedom is complete during Ramadan. There is no obligation to carry a lantern as in other months. The sparkling streets obviate this police measure.”

Source of inspiration for literature

The days of Ramadan, when the oil lamps illuminated the streets, were a source of inspiration for literature for centuries, reflected in the poems of the empire as it encompassed all parts of life. The poets wrote special verses for this month called “Ramazaniye.” Booklets titled “Ramazan-name” were published. Iftars, the meals that break the fast in evenings, were set up in beneath verses lit between the minarets of the mosques, known as “mahya.”

The spiritual changes within people were also depicted. For example, in the 17th century, the poet Sabit notes that even alcoholics turned their drinking jugs into those for ablution to honor the month. The masters of poetry – Sheikh Galip, Sururi¸ Enderunlu Vasıf and Fuzuli – often penned these kinds of verse.

From the 19th century, when literature turned more toward prose, many essays and letters began to be written to explain Ramadan. Literary figures expounded upon the zeal with which Ramadan in Istanbul was celebrated in their columns alongside sometimes cynical and sometimes joyful cartoons. Again, some illustrations focused on Ramadan highlights – such as the spotting of the Ramadan crescent, invitations to iftars and sahurs (the meal enjoyed before dawn), kites rising from the courtyards of mosques, night baths, entertainment lasting until dawn and cartoonish gluttonous types at their dining tables – can be seen in the novels as well.

Ahmed Rasim portrayed the Ottoman Ramadans with particular detail in the pages of Turkish literature. In his book “Ramazan Sohbetleri” (“Ramadan Talks”), he compiled a series of stories, memoirs and essays that everyone can enjoy. This classic work is waiting to be translated for Muslims all around the world.

Both the common Ramadan sights of the period and those prior are reported on. In the old winter Ramadan months described in these works, people used to gather in the houses for tarawih prayer and then have pleasant chats lasting until sahur. During these talks, known as “Helva,” many favorable manuscripts such as the Sahih of al-Bukhari, the Qisas Al-Anbiya or the works of Rumi were read.

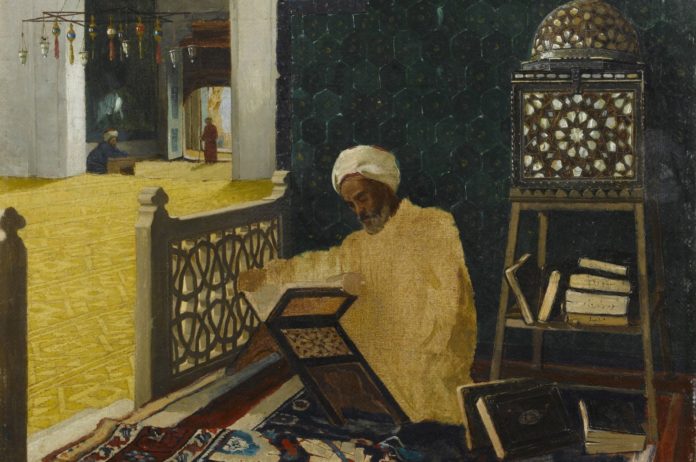

“Peace Classes” were also attended by the sultan at the palace, which saw the liveliest of talks about science and culture. The oil painting by painter Hüseyin Avni Lifij offers a cross-section of these lessons.

Famous French historian Francois Georgeon also precisely detailed the historical aspects of Ramadan from the Ottoman to the Republic. The author depicted how Ramadan was welcomed by the public, how it affected daily life and what changes it causes – especially in key districts around Istanbul. He analyzed the religious characteristics of Ramadan, its transformation in the tradition, its effect on commercial relations and – most importantly – the changes it faced in the transition to the modern period.

Ramadan in the modern world

The shifts that occurred with the fall of the Ottoman Empire and modern revolutions have all but extinguished this atmosphere. The joy of the Ramadans of former years is no more. The modernization of both the city and the state and the westernization of the society brought about a lowering of Ramadan’s importance.

This month, however, people will not forget the traditions, memories and joys of previous eras. Ramadan is a universal reality. Although secular life strikes the social mobility that comes with it, Muslims all around the world preserve the atmosphere of this month.

Amy Hackney Blackwell’s “Ramadan” is one of the best books in describing how the month plays out across the Muslim world. The book is enriched with photographs of scenes spanning from across Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, North America and Australia, comparing the differences of each country and city to others. After you finish the book, the common aspects of Ramadan and the spirit of unity in the Muslims all around the world are bound to stay with you.

Today, images of Muslims all around the world are a particular subject of photographers as well. We see that various figures and symbols belonging to this month, especially the crescent motif representing Ramadan, are favored by painters and illustrators, because there is always excitement in waiting for the crescent. This can be seen today, just as it is in old literary works. That’s why the crescent is identified with Ramadan.

As long as daily life continues to be in sync with art and especially literature, Ramadan will continue to preserve its actuality. As long as social life changes at the end of every 11 months, Ramadan will remain an inspirational source of art.