As its latest arts event accessible from home, SALT Online is screening a documentary about Cuba’s National Art Schools in the midst of revolutionary politics.

ot long after the Cuban Revolution, guerrilla leaders Fidel Castro and Che Guevara played a round of golf at one of the country’s most prestigious country clubs. Outfitted in their characteristic military duds and chewing cigars, they smiled while putting to the sound of contradiction. To their burgeoning communist ideals, such an elitist institution would come under fire, compelling many from the moneyed classes of postcolonial Cubans to emigrate to the United States, where their deep pockets would remain at their hips.

But the fabled insurrectionists were not there to score par. They conceived the space as a plot on which to build what would become known as the National Art Schools of a new, utopian Cuba. However, it was a dream that – marred by the pitfalls of socialist development, particularly as concerns arts funding – has come to symbolize the post-revolutionary ambiance of Cuban society since the 1960s, its lack of stability, hypocrisies and fleeting moments of inspired tenacity, vainglorious fantasy and creative perpetuity.

The 2011 film, “Unfinished Spaces,” by Alysa Nahmias and Benjamin Murray, is an evocative historical portrayal of a country and its people. The institutionalization of Cuban art is a byzantine narrative rife with political intrigue. The documentary by Nahmias and Murray takes as its chief subjects the architects of the National Art Schools in Havana, whose star-crossed affair with liberal development in Cuba becomes poignant through their able lens, effectively situating architecture as a pivotal sector that may bridge or divide politics and art.

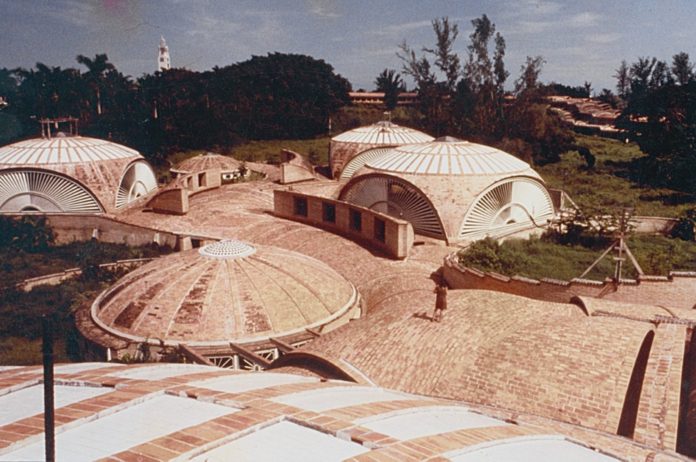

Led by Cuban national Ricardo Porro and Italian immigrants Roberto Gottardi and Vittorio Garatti, the men rose to the occasion under Castro’s nascent government and within months drew blueprints and started constructing a variety of departments, from plastic arts to modern dance, ballet, theater and music. Footage from the building site shows workers on the ground answering to the architects as they revised on the spot and experimented with techniques that continue to impress the international community.

With a mind for the people

The designs concocted by Porro for Havana’s National Art Schools are stretches of the bodily imagination. He had a penchant for feminine contours. The bulbous roofs that surfaced out of his drawings are only matched in their brazen protuberance by his sculpture of a halved, ripe papaya, which he set as part of a fountain center-stage within the complex. A leisurely sort, Porro interviews for “Unfinished Spaces” from a studio loft in Paris, surrounded by exotic art, and is even shown sensually sculpting his own work.

His fellow architect Selma Diaz, in contrast, appears for the camera in transit, somewhere on the street, presumably in Cuba, recounting the fated afternoon when a car rolled up beside her and out of its window popped the unmistakable visage of Castro, who then proceeded to ask as if extempore if she might design the National Art Schools he was planning to bankroll under the young, quixotic regime. Diaz tells the story a half-century later still with a bewildered expression, equally flattered and exasperated.

She showed up at a cocktail party in which Porro was then entertaining guests and asked him to be a part of the project. He agreed almost immediately, while not without a sense of incredulity, perhaps also a touch of suspicion. Together with Gottardi and Garatti, the trio embarked on a historical feat that, mixed with the volatility of the greater state of their nation, endures more as a testament to political and creative ambition than as the foundation of a pioneering arts education in Cuba.

In contrast to Porro’s windfalls of luck and success in Paris as a Cuban emigre, Gottardi stayed in Cuba, and Garatti eventually resettled in Milan. The Italians appear to have aged worse. At one point Porro asserts that he was never a man to pick up arms for a cause, but that he was always willing to contribute to a national struggle, and to his beliefs with ideas. For most of the projects, their familiarity with the arts was not complete. While everyone knew of visual arts, modern dance, for example, was alien to them.

Power, architecture

Porro took the lead on the buildings for dance because he was enamored with its bent to African folklore and for plastic arts, being a sculptor. Gottardi helmed the Dramatic Arts School, as a lover of theater. He is generally the more sober of the outfit, venting deliberate monologues for the documentarians in a dark studio, seemingly burdened by the weight of such debacles as befell him and his comrade architects in the upswing of midcentury Cuba.

Garatti, a wiry, nearly hunchbacked elderly Milano speaks with the air of a dreamer. Having left behind aspirations to become a dancer, he instead found contentment in his ability to build a ballet school. And with training in piano, his approach to the music department was equally advantageous. Much of the film follows him at home in Italy and returning to Cuba, where he walks the grounds of the derelict National Arts Schools amid countrified lands around Havana, unrelenting in his scheming optimism yet tempered by a fractured heart.

While the schools enjoyed a heyday of progressive student life, the project was soon overwhelmed by the Soviet political leanings of Castro and his communist allies. The otherwise visionary tradition of Cuban architecture that they were creating would be supplanted by such overly pragmatic industrial constructivism as prefabrication. And repulsively, Guevara himself was rallying against the enlightened milieu of youth that the National Art Schools fostered.

Although the doors of the National Art Schools were inclusive to people from across the Cuban countryside, no matter how rural and folk their communities and cultures, the politics of Soviet influence imposed an anti-intellectual stance. The architects of Cuba were split in two. Some were derogated as elite artists. And that discrimination became the order of business as usual at the offices of the Ministry of Construction under Castro’s early government.

In their twilight years, Porro, Gottardi and Garatti reflect on the battles they won erecting unprecedented structures, which have been slated for preservation by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. But due to embargoes and other diplomatic issues, such support is problematic as concerns Cuba’s patrimony. Nahmias and Murray interview artists who experienced what writer and poet Hakim Bey might call a “temporary autonomous zone,” in which young minds were given wings and poured their passions into a collective will for social betterment.

Toward the end of the film, the internationally renowned Cuban artist Kcho puts his arm around a hunching Garatti as they stroll around the empty, flooded quarters of the former music rooms at the National Art Schools. The grounds are overgrown, and in the windowless, concrete shell, they mount an art exhibition together, showing Garatti’s architectural drawings with Kcho’s visual work. It is characteristic of the resilience of a nation like Cuba, as with all human communities that, although fragmented by high-minded propensities, find solidarity.